In my current campaign setting, I'm working within the bounds of the traditional AD&D "canon," but trying to wring somewhat novel and interesting (at least to me) interpretations from it. One of these elements is the "standard model" of D&D cosmology--what's sometimes called "The Great Wheel."

As portrayed, it's a bit literal and mechanical, which is a shame because at its core its a crazy enough mashup concept to appear in a mimeographed pamphlet left in public places. Bissociation should be the watchword here. Or maybe multissociation? I think the planes can (and should) be both other realms of consciousness and physicalities. Conceptual overlays on the material world, and places where you can kill things and take their stuff.

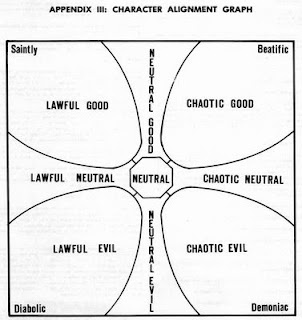

To that end, I decided to riff on the concepts of the planes, and see what associations they brought out. Not all of these will be literalized in the version of the planes visited by adventurers from the world of Arn, but all of these associations might inform how I presented the planes and the alignment forces they're of which they're manifestations or vessels. Maybe later I'll get into all the heady faux-metaphysical theory I devised behind all this. Or maybe I'll xerox my on crackpot tract.

Anyway, I figured the best place to start was a trip to hell.

The Abyss: The Abyss is the best place to start as it was probably the first of these planes to exist--the formless, primordial chaos, tainted only by Evil. An Evil that emerged, ironically, only after a material world appeared to be appalled at, and to yearn to destroy. Without creation, destruction would just subside into roiling chaos. AD&D cosmology gives us 666 layers to the Abyss, but I suspect the Abyss is infinite. Maybe its the demon lords that number 666--and the so-called layers are really the lords. Maybe all the other demons are merely extensions of their substance and essences--their malign thoughts and urges accreted to toxic flesh. They're like a moral cancer maybe, seeking to metastisize to other planes and remake them in their image--or maybe madness is a better analogy, if we're talking about the kind of madness that afflicts killers in slasher films. A psychokiller madness on a universal scale.

Tarterus: This plane is later called the Tarterian Depths of Carceri or just Carceri. I'm calling it the Black Iron Prison, because it fits, and because it recalls Phillip K. Dick's VALIS and The Invisibles. It's called the prison plane--which the Manual of Planes interprets a little literally. Not that it isn't all the obvious bad things about prisons, but its also got a Kafka-esque quality, maybe. Most souls don't know why their there and don't remember how they got there. And watch what you say 'cause the bulls have informants all over. You wait and wait for a promised trial that never comes. I suspect souls get "renditioned" from the material plane and brought here for angering a god or an Ascended. The gaolers (as Lovecraft would have it) are the demodand or gehreleths. Demodand is an interesting name as it probably comes from Vance's "deodand" which is a real word meaning "a personal chattel forfeited for causing the death of a human being to the king for pious uses" which may (or may not) hint at some sort of origin for the demodands/gehreleths. It's also interesting that the kinds of demodands--shaggy, tarry, and slime--are all related to things that can sort of be confining or restricting.

Hades: Later called the Gray Waste (a better name, I think), it's a plane of apathy and despair. There's some Blood War nonsense later, but apathy and despair is a theme to conjure with. It makes me think of Despair of the Endless from Sandman and her somber realm of mirrors. The Gray Waste is depression and hopelessness actualized. Not the sort of place for adventures, maybe, but a place good for some creepy monsters to come from.

Gehenna: Later called the Fourfold Furnaces, or the Bleak Eternity of Gehenna. This is the plane of the daemons, later yugoloth--which is suitably Lovecraftian. Daemons I liked in Monster Manual II because they were sort of "the new fiends" that seemed fresher than demons and devils, which were kind of old-hat by that time. As neutral evil, the daemons have nothing to motivate them but evil, really. The various alternate names of the plane make me think of Jack Kirby's Apokolips and its ever-burning fires--Gehenna has an assocation with fire anyway, going back to its origins as the Valley of Hinnom. Like the denizens of Apokolips, I think daemons should represent evil in various forms from banal to sublime. The Bleak Furnances fire the machineries of war. Being close to the realm of lawful evil, they sometimes dress up in the trapping of law, but its just fancy uniform facade. The whole place might appear as an armed camp run by tin-plated fascists. There are secret police, and propaganda bureaus, and sadistic experiments.

The Nine Hells: Later Baator, which doesn't work as well. This is the realm of the fallen--not the romantic, Miltonic rebels, but the fascist generals who tried to stage a junta and got exiled. Sure, they dress it up in decadence and "do as thou wilt" but really they're all oppressive laws and legalistic fine-print. And every one of them thinks they'd be a better leader than their boss, so they plot and scheme while playing it obsequious and dutiful. Some of the devils might say they're still fighting the good fight--that they do what they do to preserve the system from the forces of chaos. A multiverse needs laws after all, they say. That's all just part of the scam. Still, I like China Mieville's idea of New Crobuzon having an ambassador from hell. Maybe no city in the world of Arn has an infernal ambassador, but at least Zycanthlarion, City of Wonders, has sort of a "red phone" that can get a high-placed devil on the line. After all, better the devil you know...

4 hours ago