Friday, August 21, 2020

Weird Revisited: Draconic Correspondences

Chromatic Dragon Colors & Alchemical Associations:

Black: lead, vitriol (sulfuric acid), fire, the smell of sulfur, putrefation, phelgmatic.

Blue: tin, rust, water, acrid smell, dissolution, melancholic.

Green: copper, earth, saltpeter, chlorine smell, amalgamation, sanguine.

Red: iron, air, sodium carbonate, rotten egg smell, separation, choleric.

White: silver, alchemical mercury, after a rain smell, unemotional.

Monday, August 17, 2020

Insurgent Middle Earth

In the modern era, Sauron's forces have been engaged in a protracted occupation of Eriador. Through the action of the Mordor proxy Angmar, the Western kingdoms of Man were shattered, much of the population fled south, but fanatical bands, the Rangers, structured around the heir to throne of Arnor and Gondor, and supported by the Elves, continued to fight an insurgency against Mordor's Orcish forces and her allies.

Sauron has been a distant and not terribly effective leader for sometime. He has been unable to consolidate Angmar's victory over Arnor (a victory that saw Angmar destroyed in the process) and unable to wipe out the remaining Elvish enclaves and human insurgents.

You get the idea. Shorn of much of it's epic fantasy trappings, Middle Earth becomes a grittier place, where Men, Orcs, and local Elves, are all dealing with the aftermath of a terrible war wrought by super-powers that they perhaps only have the smallest of stakes in, but yet are forced to take most of the risk.

Seems like an interesting place to adventure.

Friday, May 15, 2020

Post-Apocalyptic Greyhawk

A great deal of change separates the North America of the 21st Century from the future age of the Free-City of Greyhawk, sitting on the ruins of ancient Chicago. The upheaval around the Anthropocene Thermal Maximum lead to mass migrations and alteration of the landscape. Four emerging peoples would be largely responsible for shaping civilization of the Greyhawk era.

The ancestors of the Bakluni were sea nomads and climate refugees from Asia who had settled on the southern Pacific Coast of North America. Pressure from groups fleeing north from the Tropic of Cancer led their culture in a more warlike direction--and also pushed them both east toward the Rockies and northward.

The Pacific Northwest was the domain of the Suel culture. It evolved in the main from separatist groups with racial supremacist leanings during the fracture of the United States and Canada. An upper-class of "pure-blooded" nobility ruled over a "mixed race" lower class in a feudal society. The inbred ruling class commonly displayed a unique mutation in melanogenesis that led to pigmentless skin and hair, and violet eyes.

The underclass of the Suel was similar (and indeed often derived from) the peoples of diverse ethnic origin that were the primary cultural group from the Rocky Mountains eastward. These were collectively known as the Flan, though they did not initial share any real concept of national identity. Most Flan lived in small, nomadic or semi-nomadic tribes.

The final group, the Oeridians, were a people of less certain origin, but they seem, like the Suel, to be derived from North Americans of European descent, but with genetic markers indicating a significant contribution from Native American ancestry. They were a tribal people known to both the Bakluni and Suel--and employed by them both as mercenaries.

Sunday, May 3, 2020

Fighting Fists, Terror Claws, and Mechanical Horses

One thing about Masters of the Universe (and by extension likely any hypothetical rpg based on it) is that, sort of like D&D, advancement often means the acquisition of stuff. There are no mounds of gold or jewels for the heroic warriors of Eternia, though, instead they get new vehicles, the occasional animal mount, and He-man, at least, gets battle armor, flying fists, and thunder punch accessories. In other words, it's toyetic.

The other thing is these innovations aren't mass produced. All the heroes don't get battle armor any more than they all get a power sword. In the more post-apocalyptic world of the early minicomics these items are analogous to D&D artifacts.

To keep the game becoming more of an arm race than the source material is, these items should require attunement or bonding. Getting more bonding slots/points should probably be one of the rewards for advancement.

Looking around, one MOTU inspired rpg, Warriors of Eternity, takes this into account, with new bond points doled in reward for narrative goals.

|

| Skeletor levels up |

Monday, April 13, 2020

Gods of Eternia

Gods and titanic monsters are not uncommon in Eternia's Masters of the Universe mythology, but very little genuine Eternian religion is revealed in the stories. What little we know of what gods were actually worshipped only comes from the post-Great War epoch, though it sometimes purports to detail events from before that era, from the time referred to as "Preternia."

Trollans

Eternian myth is only passingly concerned with cosmogony. There is the vague notion of primordial, creator gods, but these are either destroyed or sacrifice themselves at the dawn of the universe. They leave things in the hand of custodial beings, which may in fact represent an advanced civilization the ancient Eternians encountered. These beings, called Trollans, occupy a space between archangels and trickster gods. By the time of the legends of the Randorian court, the Trollans had been diminished to elfin beings and comedy relief, perhaps a reflection their decreasing importance next to Goddess worship.

Serpos

Serpos was titanic, three-head serpent worshipped by the Snake folk, a people said to have been created by a renegade Trollan. The Snake folk are said to have unless their god to level entire cities in their bid for conquest. The Snake folk dominated much of Eternia in the Preternian period and after their defeat and purported exile, Serpos was reinterpreted as either a destructive primitive aspect of the Goddess or her offspring.

The Goddess

The Goddess was typically depicted wearing a cobra headdress and sometimes with green skin. While some scholars have connected the headdress with Serpos and the Snake folk, others view it as predating the Snake folk's arrival. The green skin possibly links her with vegetation and life, allying her with the forest deity who appears in the mythos as Moss Man.

The serpent-themed Goddess initially seems predominant in the Eternos region, but immigrants from the northern plains identified her instead with an Eternian bird of prey. By the Randorian era, the Sorceress of Grayskull, held to be the Goddess' living incarnation and oracle, was garbed in feathered raiment.

|

| Art by Gerald Parel |

Thursday, April 9, 2020

Eternian Armsmen

Within two centuries the Armsmen underwent significant changes. While many still served as mercenaries, they had developed into a quasi-religious military order with the technology of the Ancients venerated as relics. Technical manuals were treated almost as liturgical texts. While the Armsmen were still formidable fighters, their focus was more on the location and recovery of lost technology.

By the time of the folk hero "He-Man," it is believed that the Armsmen no longer existed as a cohesive cultural group, but some families and small sects held to some or all of the Armsmen's practices. The Man-At-Arms of the Masters of the Universe legends represents a hermitic example of the dwindling, latter-day Armsmen.

The elite Eternian Guard of the Randorian era were depicted dressed in the "classical" armor of the Armsmen, though most scholars believe any lingering Armsmen belief were at best vestigial by that point, a testament to the Armsmen's enduring cultural cachet.

Sunday, April 5, 2020

Eternian History Revealed

Eternian historians tend to agree that aspects of the Masters of the Universe myth and literary cycle are rooted in fact, though the historicity of any given aspect of the corpus is likely to be a matter of debate. There several recognized strata of textual sources forming the cycle, each paralleling a series of popular entertainments on Earth. Earth scholars have been slow to treat the Masters of the Universe mythology as an area of serious study, in part due to the bowdlerized form of its transmission, but also to the fanciful, even frivolous translations, done to serve the needs of a toyline.

The name of central figure of the mythos, for example, is risibly rendered as "He-Man." While this is not a wholly inaccurate, literal translation of his title[1] in the earliest texts (which could be read as something like "Supreme Man" or "Male Exemplar"), it seems to have been understood as something more like "Powerful Hero" or "Mighty Person" at the time those texts were written. Such carelessness is rife in widely available translations.

The most widely known version of the mythology forms what is essentially the "Matter of Eternos," particularly focusing on King Randor and his court. The term "Masters of the Universe" arises from this era and refers to the elite warriors, comparable to the Knights of the Round Table, whose exploits are primary focus of the various epics and romances. He-Man is central to these stories, as the secret, heroic identity of Randor's son Adam, who is otherwise portrayed as callow or even foppish. He-Man's inclusion is unhistorical, but the Randorian Renaissance is a matter of historical record, and some of this Masters of the Universe are likewise attested.

The historical He-Man is believed to belong to the oldest strata of tales. These stories are simpler and portray a more primitive world still suffering the effects of the Great Wars, far removed from the technological rediscovery and courtly sophistication of Randor's time. This He-Man is a folk hero who leaves his tribe to began taming or reclaiming the wilderness. He contends with monsters and personifications of cultural competitors.

One of the key events in these early myths is He-Man's encounter with a green-skinned sorceress who gifts him with ancient weapons and armor from a cache hidden in a cave. In some myths of this strata, she is referred to as a goddess. The confusion regarding her identity likely later editing of the stories to preserve the importance of the Sorceress of Grayskull or her cult.

The earliest depictions of the Sorceress/Goddess show her in a cobra headdress. Many scholars believe this to be an important and revealing historical detail, reflecting the continued influenced of the Serpent centered religion of the conquering Snake Men. In contrast, by Randor's time, the Sorceress is clad in feathers and associated with the Eternian falcon, the Snake Men and their cultural having been thoroughly demonized.

______________________________________

1. Initially the title was thought to have been the character's actual name, but it appears in other records of that era clearly not referring to the hero. Perhaps the Eternian chroniclers were unaware of his original name among his tribe. This lack of identification is considered significant by those who doubt a single He-Man existed historically, instead viewing him at best as a composite of several real individuals, if not completely mythological. Some have seen Wun-Dar of Tundaria as the original of the He-Man character, noting the similar stories told about them, but it seems more likely some of He-Man's exploits were attributed by the Tundarians to their local hero.

Friday, April 3, 2020

Weird Revisited: The Ahistorical Historical Setting

|

| Historically accurate Aristotle? |

The changes can be big. Reign: The Conqueror (based on the novel Arekusandā Senki by Hiroshi Aramata) re-imagines the life of Alexander the Great as a sort of science fantasy thing with giant Persian war machines and Pythagorean ninjas. Or, they can be subtle, like Black Sails weaving historical pirates with a sort of prequel to Treasure Island. (The difference I see between this last one and a standard historical setting which would generally tend to insert fictional characters, i.e. the PCs, into history, is the "high concept" of the literary/historical mashup.)

|

| A lesson on Greek myth every week? |

Let history be your guide, not your boss.

Sunday, March 29, 2020

A D&D Party as Skillful Companions

Noting that D&D characters (and rpg characters) are defined by classes, races, and player chosen abilities that make them ideally different from the other characters in their party, I going to suggest that D&D adventures really click when they work a bit like a Skillful Companions tale: when ever player gets to contribute their thing and their thing helps the adventure reach a happy conclusion.

I think "player skill" and creative solutions to problems should of course play a part in rpgs. Players derive more satisfaction from solving problems when they feel like they did it, not just their characters. But contrary to some not infrequently repeated old school wisdom I think the answer should sometimes be on your character sheet, or at least the tool your going to leverage to derive the solution ought to be. Having different character types or arrays of spells, weapons, and other abilities having mechanical differences would be inexplicable otherwise.

Adventure design for an unknown group of players obviously has a hard to tailoring challenges, but I think if you're making adventures for your regular group, maybe they should be crafted with the players in mind. There should never only be one way around a problem, of course, and player's can and should be able to avoid encountering a problem entirely, but there's nothing wrong with at least thinking of things that might give each character their time in the spotlight.

Friday, March 27, 2020

Setting Creation: Patchworks & Found Objects

To an extent, almost all world-building relies on borrowing, it's just a question of the size of the blocks being borrowed. Robert E. Howard's Hyborian Age can show its inspirations pretty nakedly in places like Vendhya or Asgard, but even Tolkien's less derived-appearing subcreation has pretty clear analogs like an Atlantis myth. It's not surprising really; real world sources are built on foundations of history; completely imaginary cultures are not only harder to come up with, but also less detailed and less well thought out. The real question is how are these borrowings used?

Mystara (The Known World) is what I would call a patchwork. Its sources are almost always pretty obvious (and the writer's tell you what they are just in case you missed it), and they are stitched together with not much thought to realism. Patchworks have the advantage of being easy to get a handle on for GM or player, but run the risk of hampering the ability to create a vivid, new world. It's also easy for things to run to stereotypes and unintentional comedy, perhaps.

The other form of the borrowing in settings is the one I called the found object. Here the borrowed blocks are smaller, or less overtly recognizable, and they are used in a more transformed fashion. Howard's Hyborian Age actually straddles the border between patchwork and found object. Some of this, admittedly, may be the remove between our pop culture adventure fiction and that of Howard's day. It may be his sources were more obvious in the 1930s. But in any case Asgard as a "Viking culture" and Stygia as "evil Egypt" are pretty big patches. Nemedia gets a little harder to recognize. It's mostly "rival Medieval nation" but its elements of Holy Roman Empire aren't too difficult to see, and it also has details like a band of Northern mercenaries like the Byzantine Varangian guard. Then there are a few lands that are more obscure: Khoraja, for example, has a (Near) East meets West thing going on that might remind on of Howard's historical actioners in the Outremer, but also likely Trebizond.

Tolkien did this sort of thing, too. The Arnor/Gondor divide just changes the cardinal directions of the Roman/Byzantium split, in a way that mirrors the Israel/Judah divide. The Dunlending/Numenorean conflict has echoes of the Anglo-Saxons versus the Celts in the British Isles. These things are there without the borrowing being complete or obvious.

Is there a downside to the found object approach? Well, if the borrowings are too obscured you don't get any advantage of easy recognizability, which might be a problem if you are making a product to sell or trying to communicate things quickly to players. But you still get most of the advantages of patchwork for ease of your own work on the setting.

Thursday, March 26, 2020

Conan, 1963

William Smith as CONAN

Former Miss Israel and Bond girl Aliza Gur as YASMINA

Jack Palance as KARIM SHAH

Christopher Lee as THE MASTER OF YIMSHA

Raf Baldassarre as KHEMSA

and Chelo Alonso as GITARA

Sunday, March 8, 2020

East of Caldwellia, West of Elmoreon

The visuals are clear and distinct, but is there a setting in the work of these artists distinct from just generic D&D?

I'm not entirely sure, but I think we can say make guesses as to what elements it may have and what elements it does not.

Glamorous Not Grotty

Glamorous might be a little strong, but hey, alliteration! Anyway, we are certainly not in the Dung Ages, or any version of gritty pseudo-Medieval verisimilitude.

Complicated Costumes and Culture

Compared to work of Frazetta, Kelly, or Vallejo, the clothing of the characters has a lot going on: fur trim, feathers, scales, etc. This tends to be true even when female characters are scantily clad. It's all more renfair that Conan. This suggests (to me) more of a high fantasy world than a sword & sorcery one, and an interest in visually defining cultures that doesn't get into the heavy worldbuilding of a Glorantha or Tekumel, but is definitely of the "needs a glossary at the end of the book" level.

Dragons & Drama

There are an awful lot of dragons. I mean, they're showing up all the time. And often characters are confronting them in a way that suggest they are big, powerful heroes, not the type to die pointless in holes in the ground. The another name for high fantasy is epic fantasy, and that's what these images often convey.

A Touch of Humor

Despite the epicness and high drama, things are seldom if ever grim. In fact, from adventures posing with the tiny dragon they slew, to a muscular female fighter manhandling an ogre, a bit of humor is pretty common.

Monday, February 24, 2020

Talislanta: The Sarista of Silvanus

|

| French Talislanta art |

Tamerlin's account tells us they are "a nomadic race of indistinct origin," and they are of "slender proportions" and have "skin the color of rich topaz, dark eyes and jet black hair." (Again with the topaz skin! I suspect their origins to be Phaedran, then whatever the mystery.) They tend to dress in a gaudy, ostentatious, or seductive way (their clothing sounds theatrical, to me), and they are known as "folk healers, fortune tellers and performers--or as mountebanks, charlatans, and tricksters."

These things are stable across all editions of Talislanta, with only minor differences in the text. Sarista have the distinction of having had a supplement devoted to them in the third edition, and are also otherwise fleshed out in the deuterocanonical Cyclopedia Volume IV. That work reveals the Sarista to be the descendants of criminals, witches, and various nonconformists that fled Phaedra when the Orthodixists took over. It also suggests that Saristan fools are called Rodinns after the ancient wizard.

"Let them scoff as they see fit! I will never compromise what I consider my art, especially for the sake of gain!"

"For the sake of gain I’d compromise the art of my grandmother,” muttered Zamp under his breath.

- Jack Vance, Showboat World

I think I would de-emphasize the "gypsy" aspect of the Sarista, and certainly dispense with distasteful stereotypes like child-stealing, to portray them as perhaps less an ethnicity and more a vocation or society. The texts mention that the Silvanus Wood isn't conquered by the Aamanians because its the kind of playground/preserve of the nobility of Zandu. Sarista are part theater troupe, part carny. They make their living traveling the forest circuit performing for their mostly Zandu visitors, and fleecing the rubes as they can. Sure, some may be outright thieves, but not near so many as the texts suggest--that's just prejudicial slander.

Friday, February 21, 2020

Weird Revisited: Hard Science Fantasy

|

| Art by Bruce Pennington |

Genre titles are really imprecise things, so let me explain what I mean: A setting that looks like fantasy, but is in fact sort of post-technological science fiction. What would make it "hard" as opposed to the usual science fantasy is that it wouldn't resort to what are essentially fantasy concepts like extradimensional entities or psionic powers to do it. The fantastic would come from at least moderately more possible sources like near Clarketech ("any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic") nanotechnology, cybernetics, and bio-engineering.

I haven't really seen this out there in gaming. Yes, Numenera presents a world utterly drenched in nanotech that can be tapped like magic by the masses, ignorant of it's nature. But Numenera still has psychic powers and extradimensional monsters. What I'm envisioning is more like Karl Schroeder's Ventus (where the "spirits" animating the natural world are AI controlled nanotech) or the Arabian Nights-flavored Sirr of Hannu Rajaniemi's The Fractal Prince where spirits in ancient tombs are digital mind emulations and the jinn are made of "wildcode" malicious nanotech.

Beyond nanotech, monsters would be genetically engineered creations of the past or descendants thereof. Or perhaps genuine aliens. Gods would be post-human biologic or AI entities--or often some combination of both. Or figments of human imagination. Or leftover bombs.

Why a more "rigorous" science fiction masquerading as fantasy world than the usual Dying Earths or whatnot? No real reason other than it seems to me starting with far future science fiction and figuring out how it would be rationalized by a more primitive mindset might yield a fresher take on the standard fantasy tropes.

Thursday, February 20, 2020

My Secret and Possibly Quixotic Yearning for Vanilla

Since I've entered the blogosphere (over 10 years ago now), I've imagined all sorts of variants of D&D-type fantasy from Weird Adventures to the cyberpunk planes City of Gyre, I've often even eschewed weird in the classic "Weird" sense. My takes were hardly even the most out there among the DIY crowd in which I have often found myself.

But there are times when I think back with nostalgia to a sort of game I never really played. Or games, I should say, it's not always the same. Sometimes it's nostalgia for fantasy before D&D was a thing, something like a mix of Byfield's The Book of the Weird, Alexander's Chronicles of Prydain, and the film versions of The Last Unicorn and The Hobbit. Other times, I think it should be a bit grottier, like the World of Titan, and the illustrations in the Fighting Fantasy books, and more adventure-y like select illustrations from the Moldavy-Cook editions and the earliest AD&D books. The rarest, least frequent itch is for something like the illustrations of the "High D&D" era defined by the likes of Elmore and Caldwell.

All very vanilla, I know. Our elves aren't different, they're just elves. Feudal Kingdoms, bearded wizards in towers. All the tropes!

I don't really know what the yearnings about. Some of these things were the inspirations of my pre-D&D days, so maybe its sort of the world that had moved on before I was old enough to take part in it. Others, well, they were maybe what was in the gamebooks I was playing with, but I was ignoring it in favor of the stuff I was reading--comics books, Edgar Rice Burroughs novels, Conan yarns.

Of course, its all relative. I'm sure some people think my Land of Azurth game is pretty vanilla, but to me is too knowing to be that. Maybe that's why I never pull the trigger on a game inspired by one of these things. Still, it's something I think about.

Thursday, January 30, 2020

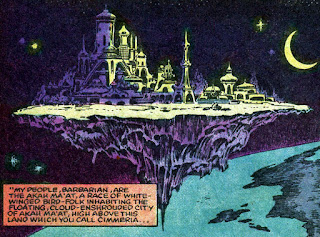

Omniverse: Birds of A Feather

There is a lost city, hidden by the clouds, drifting slowly above the modern world, every bit as silent as the tomb it has become. This was the city of an ancient civilization of winged humanoids, the Bird People. It had existed for eons before the future king of Aquilonia, Conan, came to it some 12,000 years ago. It was called Akah Ma’at, and its people were at war with the bat-winged humanoids of Ur-Xanarrh, something Conan helped them with.

The Hawkmen of Mongo may well be the descendants of an abducted group of Bird People. The cannibalistic hawkmen Travis Morgan encounters in Skartaris are certainly of the same lineage.

It may be that Akah Ma’at meant “Sky Island” and eventually came to mean “Aerie,” because when they clouds recede again, and the city appears in the modern historical record, those are the names it is given in translation. In the 1920s, an airplane because lost in a storm and crashes into the Sky Island. A young boy was the only survivor. He was taken in by the Bird People and would be the costumed hero Red Raven1.

It is possible that the hero Black Condor (Quality Comics) represents the same individual, since the Black Condor’s origin as related in the comics of being raised by condors in the Gobi seems implausible--and not just because condor's are native to the Americas. Perhaps the Bird People were in the habit of taking in foundlings?

Red Raven eventually had to turn against his adoptive people when their warrior class, under the influence of the Bloodraven Cult of demon-worshippers, sought to make war on the surface world. The ensuing civil war destroyed part of the city and ended with population either fleeing or placing themselves in suspended animation. The city was left in the charge of two android Bi-Beasts who would later encounter the Hulk.

There is some confusion regarding the origins of the Bird People. Accounts suggest that are an offshoot of the Inhumans, but this ignores the prior existence of Akah Ma’at. Rather, there is an Inhuman offshoot people with more avian features. These are the Feitherans, the people of the superhero Northwind, who lived in a hidden city in the Arctic Circle, and also probably the Aerians that live near the South Pole in the Savage Land.

1Red Raven’s flight costume was made with Cavorite, which may or may not be the same thing as nth metal, but certainly as similar properties.

Thursday, January 16, 2020

Through A Veil of Blue Mist Did I First Behold Talislanta

I've mentioned my appreciation for Stephan Michael Sechi's Talislanta setting. Since I'm contemplating running a Sword & Planet game that uses Talislanta as the "planet," I though it was a good time to revisit the setting, and it's publication history in a series of posts, as I think about what I'm going to use and what I might do differently.

Historically, Talislanta is both a setting and a game. It's core, however, has always been the systemless Chronicles of Talislanta, first published by Bard Games in 1987. Chronicles is the narrative of Tamerlin, a wizard from another world, as he explores the continent of Talislanta. Sechi's imaginative setting is made more compelling by P.D. Breeding-Black's distinctive illustrations.

When I first encountered Talislanta, I didn't have much experience with Sechi's inspirations: the works of Jack Vance, Marco Polo's Travels, The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, and the comics of Philippe Druillet. To me, it seemed more daring than the implied setting of D&D, and at once goofier and more lurid than the likes of Middle-Earth. It reminded me of Star Wars and comic books. I liked it instantly.

My appreciation has only grown over the years. So, I'm going to trace Tamerlin's journey and the places it visits across editions and think about how I might make it my own, influenced by my understanding of Sechi's stated influences and influences of my own.

More to come.

Friday, January 10, 2020

Setting History Should Do Something

My thesis is that history in rpg books is most useful/good when it does something. Possible somethings are:

1. Helps to orient the reader (mostly the GM) to the themes/mood/flavor of the setting.

2. Directly establishes parameters that impact the player's adventures.

3. Provides "toys" or obstacles.

It is unhelpful when it does the following:

1. Describes events that have little to no impact on the present.

2. Describes events which are repetitive in nature or easy to confuse.

3. Provides few "toys," or ones that are not unique/distinctive.

Now, I am not talking specifically here about number of words or page counts, which I think a lot of people might feel is the main offender. Those are sort of dependent on the style/marketing position of the publication. Bona fide rpg company books tend to be written more densely and presumably read more straight for pleasure. DIY works are linear and more practical. My biases are toward the latter, but I am more concerned with content here. I do think in general that economy of words makes good things better, and verbosity exacerbates the bad things.

Let's get into an example from Jack Shear's Krevborna:

Gods were once reverenced throughout Krevborna, but in ages past they withdrew their influence from the world. Some say that the gods abandoned mankind to its dark fate due to unforgivable sins. Others believe that the gods retreated after they were betrayed by the rebellious angels who became demons and devils. Some even claim that the gods were killed and consumed by cosmic forces of darkness known as the Elder Evils.Looking at my list of "good things" it hits most of them. It helps orient to mood and theme (lack of gods, dark fate, unforgivable sins), it sets parameters for the adventurers (cosmic forces of darkness, no gods), and provides obstacles (demons and devils, rebellious angels, elder evils).

That's pretty brief, though. What about a wordier example? Indulge me in an example from my own stuff:

So, the good stuff: orienting to theme, mood. etc. (deep history, memeplexes, super-science, transcendence as old hat, names suggesting a multicultural melange), setting parameters (a fallen age compared to the past, psychic powers, vast distances), and toys and obstacles (psybernetics and a host of other advance tech, Zurr masks, Faceless Ones!)

But wait, have I done one of the "bad things?" I've got two fallen previous civilizations? Isn't that repetitive and potentially confusing? I would say no. The Archaic Oikueme is the distant past (it's in the name!). It's the "a wizard did it" answer for any weird stuff the GM wishes to throw in, and the source of McGuffins aplenty. The Radiant Polity is the recent past. Its collapse is still reverberating. It is the shining example (again, in the name) that would-be civilizer (and tyrants) namecheck.

Thursday, January 9, 2020

Weird Revisited: The Planetary Picaresque

We're all familiar with the Planetary Romance or Sword and Planet stories of the Burroughsian ilk, where a stranger (typically a person of earth) has adventures of a lost world or derring-do sort of variety on an alien world. I'd like to suggest that their is a subgenre or closely related genre that could be termed the Planetary Picaresque.

The idea came to me while revisiting the novels in Vance's Planet of Adventure sequence. The first novel, City of the Chasch, is pretty typical of the Planetary Romance form, albeit more science fiction-ish than Burroughs and wittier than most of his imitators. By the second novel, Servant of the Wankh (or Wanek), however, Vance's hero is spending more time getting the better of would be swindlers or out maneuvering his social superiors amid the risible and baroque societies of Tschai than engaging in acts of swordplay or derring-do. One could argue the stalwart Adam Reith is not himself a picaro, but the ways he is forced to get by on Tschai certainly resemble the sort of situations a genuine picaro might get into.

These sort of elements are not wholly absent from Vance's sword and planet progenitors (Burroughs has some of that, probably borrowed from Dumas), but Vance makes it the centerpiece rather than the comedy relief. Some of L. Sprague de Camp's Krishna seem to be in a similar vein.

The roleplaying applications of this ought to be obvious. You get to combine the best parts of Burroughs with the best parts of Leiber. I think that's a pretty appealing combination.

Friday, January 3, 2020

More on Clerics

Well, we're still left with unanswered questions regarding how the cleric class fits into the structure of religious organizations. Do all priests have spells? If so, where do they get the experience to go up in level?

Here are some possibilities drawn from real world examples that are potential answers, though of course not the only answers, to these questions. Most of these assume clerics adventure because they are "called" to in some way. Whether this is a legitimate belief on the part of the cleric and society or a mistaken one would depend on the setting.

Lay Brothers

Clerics are not ordained priests but warrior lay brethren, like the sohei of Japan or the military orders of Europe. They would overlap a bit with paladins, but that's real just a matter of whether they were stronger in faith or battle. In this version, priests might or might not have spells, but if they did it would strictly be at the dispensation of their deity.

Prophets/Evangelists

This is more or less the idea I proposed in this post. Clerics are outside the church hierarchy, though they may or may not have started there. They were chosen by their deity for a special purpose. They may be reformers of a church that has been corrupted or lost it's way, founders of a heretical sect with a new interpretation, or the first in ages to hear the voice of a new god. Priests here may have no magic or may be powerful indeed but erroneous in their theology.

Mystics

Similar to my "Saints and Madmen" ideas before, mystics are either heretics or at the very least esotericists with a different take on their religion than the mainstream one. The difference between this and the Prophet above is that they have no interest in reforming the church or overturning it, they are either hermits or cult leaders who isolate themselves from the wider world to pursue their revelations. John the Baptist as portrayed in The Last Temptation of Christ would fit here, as would perhaps the Yamabushi of Japan, or certain Daoist sects/practitioners in China. They might be not at all scholarly (with all spells/powers being "gifts of grace" unavailable to less fanatical priests) or very scholarly with powers/spells coming from intense study or mediation which even more mainstream priests cannot master.

Special Orders

Clerics are members of special orders within the church hierarchy dedicated to recovering the wealth and lost knowledge of dungeons for the the glory of their deity and the betterment of their church. Not all priests have spells. Clerics are priests chosen for their aptitude or particular relationship with the divine or whatever. These orders may be quite influential within the church hierarchy, but their mission thin their ranks and keeps them in the wilderness and away from centers of power--perhaps by divine will or by design of church leaders.